When a University Needs More Money: Part Two

Savvy university leaders leveraged “enrollment threshold” polices to create a new financial formula: more of a certain type of student = even more money.

As covered in Part One, a series of federal policies enacted in the latter half of the 20th century encouraged competition among universities, causing enrollment management to become the primary engine driving schools toward securing more money guided by a “per-student” formula:

more students = more money

As the system took hold, colleges and universities sought competitive advantages, and savvy administrators in search of more money moved from just implementing enrollment policies to innovating within them. By merging “per-student” funding policies with “enrollment threshold” policies that financially incentivized student diversity, schools began pursuing students in specific marginalized communities to generate additional tuition revenue. If schools could meet certain prescribed demographic benchmarks, they could secure bonus “pots of gold.” Some leaders discovered an altogether new funding formula:

more of a certain type of student = even more money

These enrollment incentives led to a shift in institutional strategies, captured in the response of one provost I interviewed for Capitalizing on College: “Demographics are changing; you have to be able to go where there is growth, which [for our school] is Latino and first-generation students.” The financial calculus was crystal clear in her mind—schools that failed to pursue these incentivized demographic groups would sacrifice their competitive edge, leaving those committed (in her words) to “a traditionalist [approach]” doomed to fight “an uphill battle” against their more savvy peers.

How They Did It – Interpretation as Innovation

Faced with increasing competition and the need to keep the enrollment engines running, the executives at tuition-driven schools turned what is known as “policy innovation” upside down.

Policy innovation is typically understood as the development of specific policies that aim to catalyze innovation in a sector to bring about solutions to complex issues. Policymakers craft policies to generate innovation.

But in higher education, when policymakers created an educational marketplace where universities competed for students, university leaders gradually acted in innovative ways toward the actual policies themselves to give their institutions a competitive advantage. Hidden within the ambiguous wording of education policies were latent opportunities administrators could exploit by interpreting them in entrepreneurial ways and innovatively secure more money.

In other words, innovation did not solely occur “out there” in the marketplace that policies strategically designed, but also manifested “in here” within the lines of the actual policy language. For university leaders, “policy innovation” meant making the policies themselves the object of focus. They took one policy that offered them money (“per-student funding”) and combined it with another policy (“enrollment thresholds”) that offered them even more money.

Incentivizing “a Numbers Game”?

The area of policy innovation leaders in Capitalizing on College openly embraced involved “enrollment threshold” funding associated with underrepresented students. With the system allocating funds on a per-student basis, leaders were incentivized to search for new students in new markets. An official I talked to put the matter bluntly: “All colleges are basically trying to find ways of accepting all students, because the government is handing out the money [on a per-student basis].”

But by innovatively combining enrollment-based policies through novel interpretations of their wording, school leaders figured out how to secure even more federal funding. The additional available federal funding was linked to “dynamic” characteristics of an institution (i.e., enrollment and student body demographics), which differed from the funding associated with the “static” characteristics of an institution—for example, the fixed designation of Historically Black College or University (HBCUs). As a result, while an institution cannot newly qualify as an HBCU and tap into static sources of funding, policies encourage colleges and universities to enroll enough Black students (if they can) to dynamically become a Predominantly Black Institution (PBI)—and reap the financial benefits of such a designation.

Through “enrollment threshold” policies, if a college or university’s enrollment surpassed 40% Black students, it could achieve the designation as a PBI; if student enrollment surpassed 25% Hispanic students, it could achieve the designation of a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI); and if student enrollment surpassed 10% Asian American, Native American, or Pacific Islander students, it could achieve the designation of an Asian American & Native American Pacific Islander Serving Institution (AANAPISI). Colleges and universities that possessed these designations received additional federal funding when their demographics met these specific diversity thresholds.

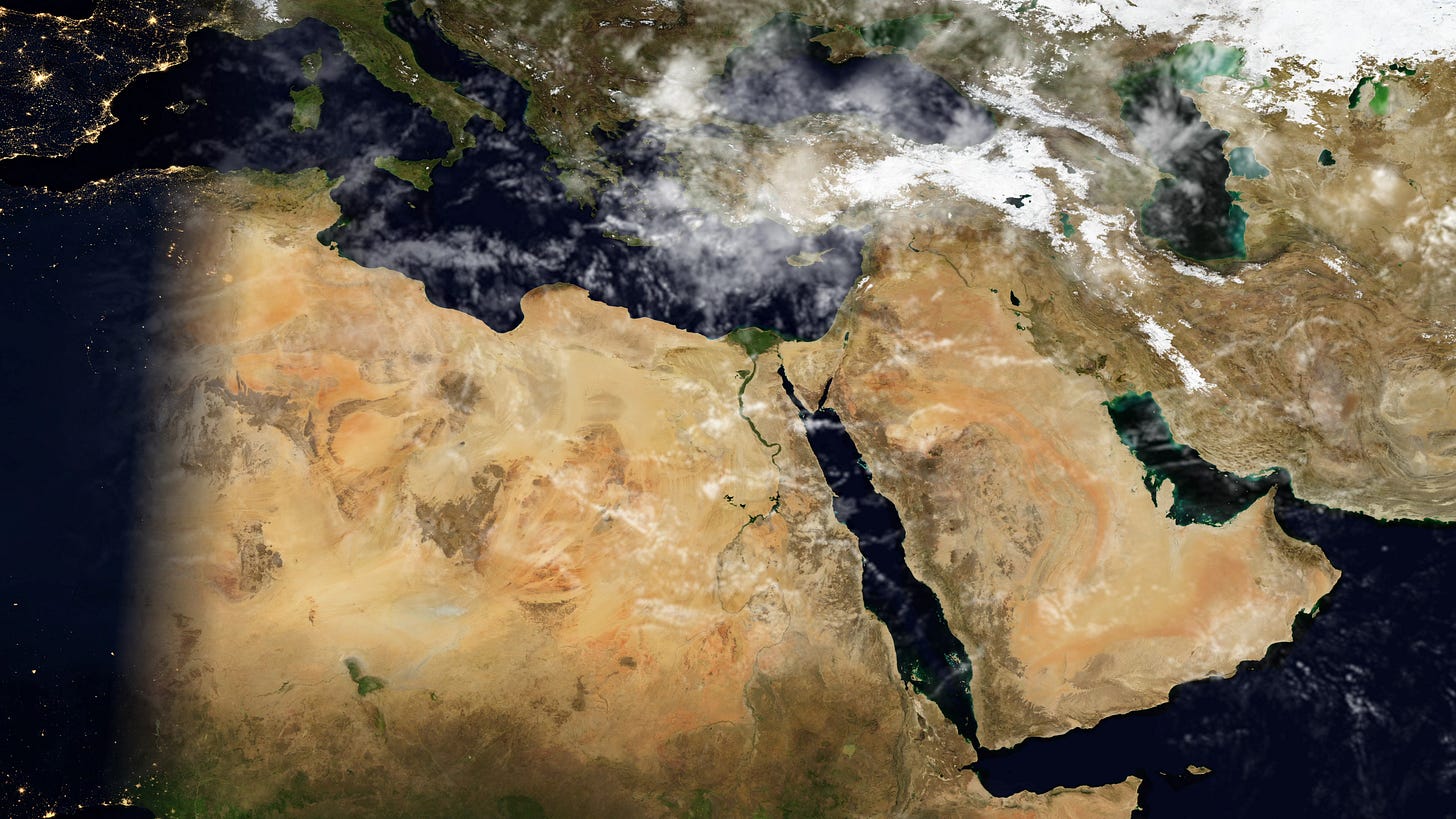

University leaders I interviewed were acutely aware of the financial resources made available at these thresholds and pivoted their attention to the most achievable enrollment thresholds for their particular institutional context. Seeing a threshold lower than the 40% required to become a PBI, and considering a surging national population among Hispanic Americans, many institutions fixed their sights on the 25% threshold required to become an HSI.

For some, it did not matter whether the school had a historical mission of serving such students or even catered to their particular needs: “Hispanic-serving institutions are basically a federal designation based on enrollment,” a senior leader clarified, and then knowingly remarked, “But what does it really mean to be a Hispanic-serving institution?” The answer was spelled out unambiguously by another vice president: “We are this close to the 25% mark,” he smiled, holding up his thumb and forefinger. From a perspective of economic reasoning, serving underrepresented students was reduced to a numbers game.

There is No Box for This

The impact of interpretation on “enrollment threshold” policies intended to support diversity emerges most clearly when comparing the incentives associated with different groups of underrepresented students. Leaders at some schools I visited had strategically labored for years to bolster Hispanic student enrollment and were ultimately rewarded with additional federal funding for surpassing the 25% demographic threshold.

However, leaders at another school also enrolled a substantial number of ethnically diverse students—but not from a population recognized by “enrollment threshold” policies. As one exasperated administrator explained about their school:

“[Our diversity] does not come out in the numbers because [the enrollment policy] counts Middle Eastern [students] as White! ... if you look at our diversity numbers, we are not considered that diverse, which is completely f***ing ridiculous!”

Despite serving a substantially high percentage of Middle Eastern students, administrators at this university were not beneficiaries of the diversity funding available to other institutions because of systemic limitations in categorizing diversity. A vice president put the matter bluntly: “Our diversity calculations are misrepresented…People do not consider socio-economic and religious diversity. They just always look at race. And if they are just looking at race, there is no box for Middle Eastern, so you click White.” He threw up his hands in exasperation. “Diversity gets lost.”

Because of the way the system had been set up, while some schools were able to successfully innovate and recruit underrepresented populations to reap the financial rewards, others were comparatively penalized despite being equally diverse. Even universities that were “organically” committed to serving local marginalized students were not rewarded the way other schools were because the populations they served were not recognized in the “enrollment threshold” policies that had been established. An administrator I spoke with at one such school offered a succinct summation of this approach to diversity: “I think it’s total bulls**t.”

For savvy university administrators, the diversity checkboxes on enrollment forms aren’t just about representation; they’re potential revenue streams. And when faced with financial pressures, the formula is clear: target the students with the highest government-assigned dollar values. After all, in the enrollment numbers game, some diversity pays better than others.

Extra Edge:

Issue Soundtrack: Keep the Car Running by Arcade Fire

Visual Scholarship: I find that images can sometimes unlock paths of learning beyond words alone. I invite you to explore this collection of helpful graphics that were created to accompany some of my writing.

ICYMI: This op-ed of mine on value entrepreneurs was recently published in Diverse, and Capitalizing on College was mentioned in The Guardian.

Dynamic vs. Static Missions: For more about the “dynamic” versus “static” missions of minority serving institutions, please see this chapter of mine “The Evolving Missions and Functions of Accessible Colleges and Universities” in an edited book called Unlocking Opportunity through Broadly Accessible Institutions by Gloria Crisp, Kevin McClure, and Cecilia Orphan.

Adding international students don't even count towards these diversity numbers and just labeled under a broad "international" category. We have a strange system here!